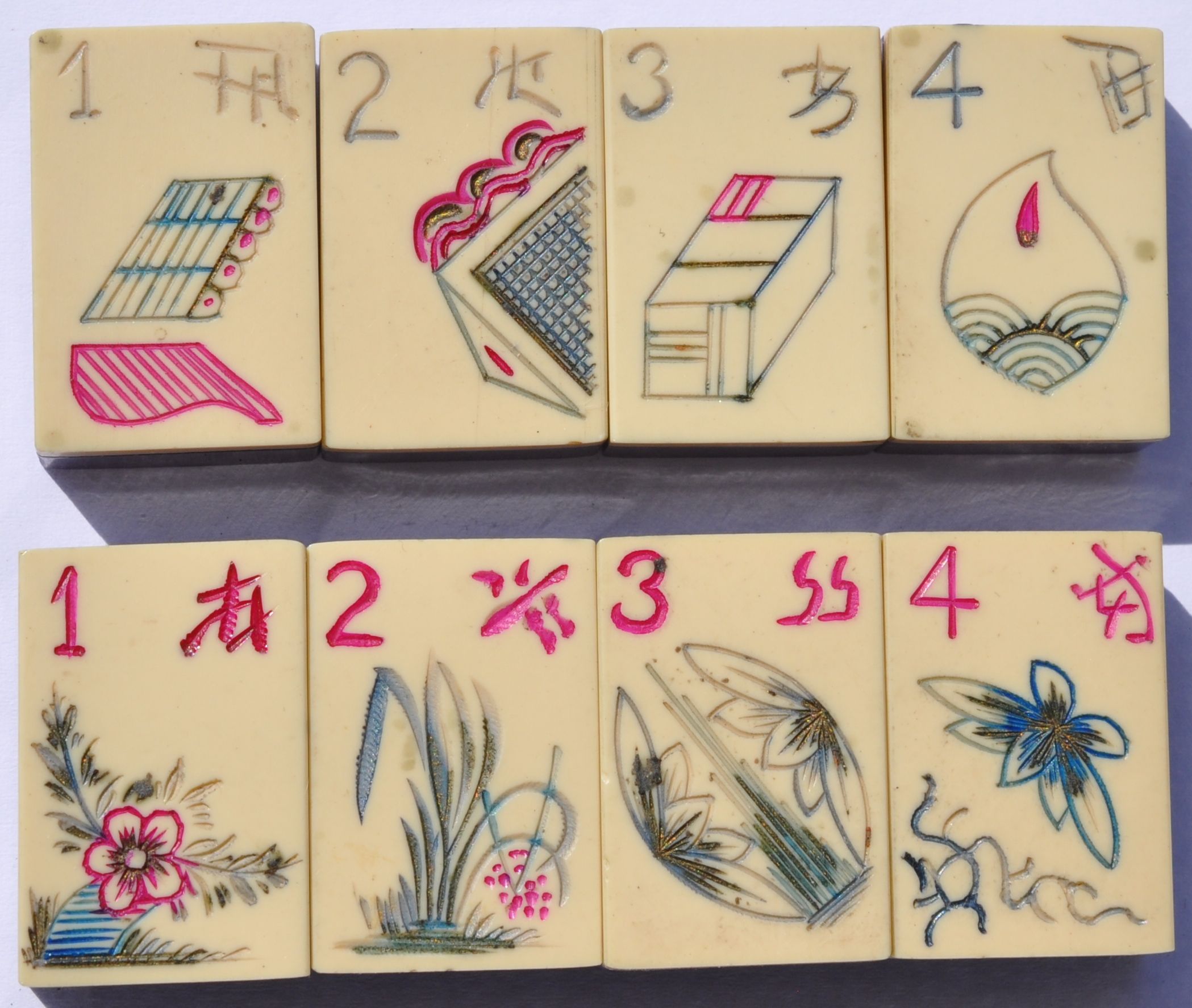

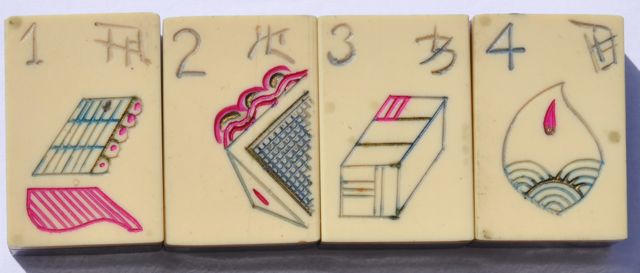

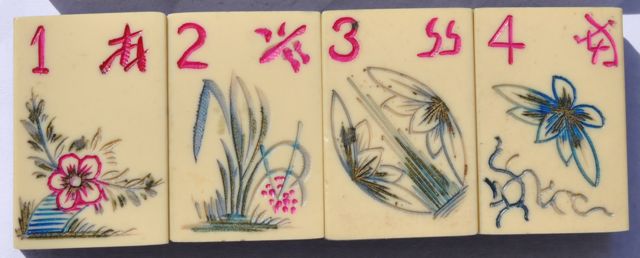

These Flowers are from the hand carved Chinese Bakelite Mahjong set we saw yesterday. The top Flowers show a female musician and three other ladies, perhaps dancers with long sleeves. The Chinese symbols are those of the seasons: Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter. A wall background is carved behind these ladies, as we often see on these type of Flowers, though the author misplaced those four tiles which should read 4321 to have the wall work! The lower set are the Singapore capture tiles, the Rich Man and the Pot of Gold, and the Cat and the Mouse.

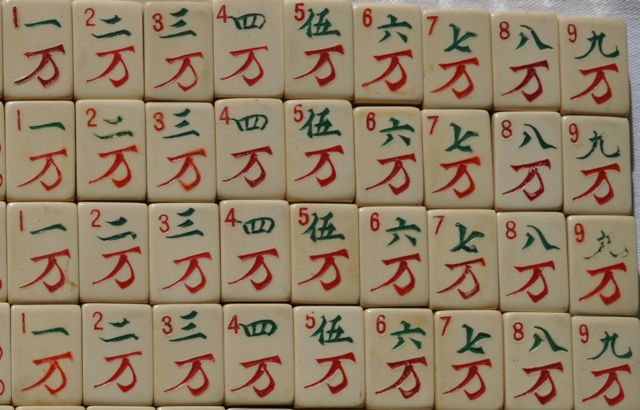

The color silver, seen above, is rare on Mahjong tiles.

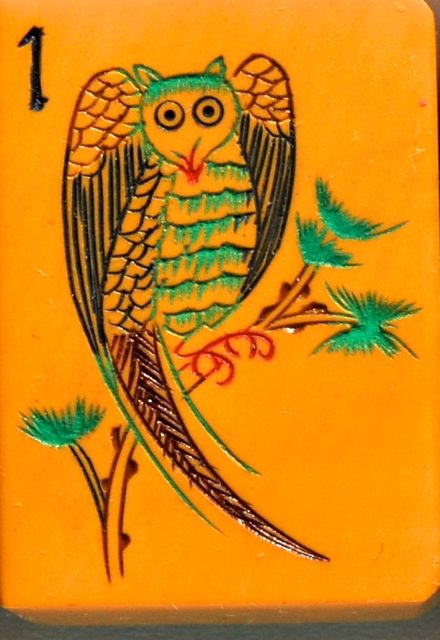

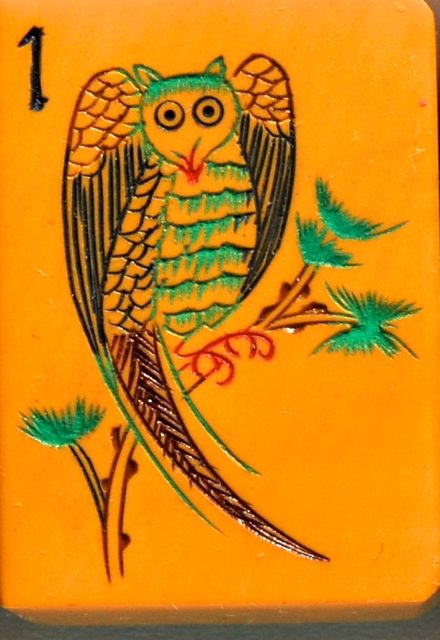

Many scholars, including C.A.S. Williams and Wolfram Eberhard, acknowledge that owls were not looked upon favorably in China in the 1900s, and rather were harbingers of ill fortune and death, unlike the phoenix which is associated with good fortune. Clearly, though, the Western market did not have those thoughts about owls.

And for a bit more about the owl in early Chinese history, Ray Heaton provided us with a link to a Sotheby's article.

http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/2014/sakamoto-n09124/sakamoto-goro/2014/02/the-owl-in-early-chi.html

Here is an excerpt I thought was interesting:

"The myth of the origin of the Shang people is found in The Book of Songs (“Heaven bade the dark bird”) . Of course, this song cannot be regarded as an original record of the Shang dynasty. It is more likely that it was transmitted orally through the Shang into the Zhou period, with slight variations over time. In Shang and Zhou lexicography, the word xuan (black) can also be understood as “mysterious” or “divine”8, and in Shang oracle bone inscriptions, we find a pictograph depicting a beaked owl with round eyes and plump torso, which is the name of a star, or it can be rendered as the character standing for the owl itself (Heji: 522, 11497, 11498, 11499, 11500). In other cases, it is used together with the ancestral names Fu Gui and Fu, and can be interpreted as “Father Gui of the Owl clan” (fig. 11) and “Lady of the Black Owl clan” (fig. 12). Thus, the evidence from Shang archaeology and historical literature render it quite possible that the Shang people believed in some mythical relationship with the owl. Liu Dunyuan has argued that the Shang people perceived the owl as the god of night and dreams, as well as the messenger between the human and the spirit world – on account of its silent flight and hunting in darkness9. If so, this would explain why the owl is employed repeatedly in Shang ritual art and is found in a burial context, as we have seen in the examples previously discussed.

The conventional explanation is that the black bird is a swallow (yanzi). This was the view of scholars of the Han dynasty, and Han paintings and murals did indeed present the swallow as the black bird (or sun-bird, taiyangniao) and the owl as the bird of the underworld. For example, the silk funerary banner from the Mawangdui Han tomb (no. 1) depicts a black bird (swallow-like) in the sun, and an owl-like bird near the entrance of the heaven, and moreover, on left and right sides of the earth platform are two owl-on-turtle images. Their meaning, according to Eugene Wang, is to signify “the sun setting at dusk in the west and re-emerging from the east at dawn.”10 Han ideology favored the association of the swallow with filial piety (xiao) – after all, the swallow faithfully returns every year – and the owl was conversely portrayed as an evil bird that ate its mother11. We however do not find such opposition in the earlier period, and in Shang archaeology, while there are a few references to the swallow, the owl is clearly more prominent."