Written by guest writer WS

In his semi-autobiographical novel EMPIRE OF THE SUN, G. J. Ballard describes what befell British citizenry in Shanghai China during the Japanese Occupation of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). It depicts events immediately following December 7, 1941, when Imperial Japan, having attacked Pearl Harbor, took over and occupied the long-established American and British settlements of the city. British and American civilians were rounded up by Japanese soldiers, and many were marched to their deaths in brutal Japanese internment camps. Ballard was lucky; his parents survived the death squads and he was reunited with them after the war.

Others weren’t so fortunate.

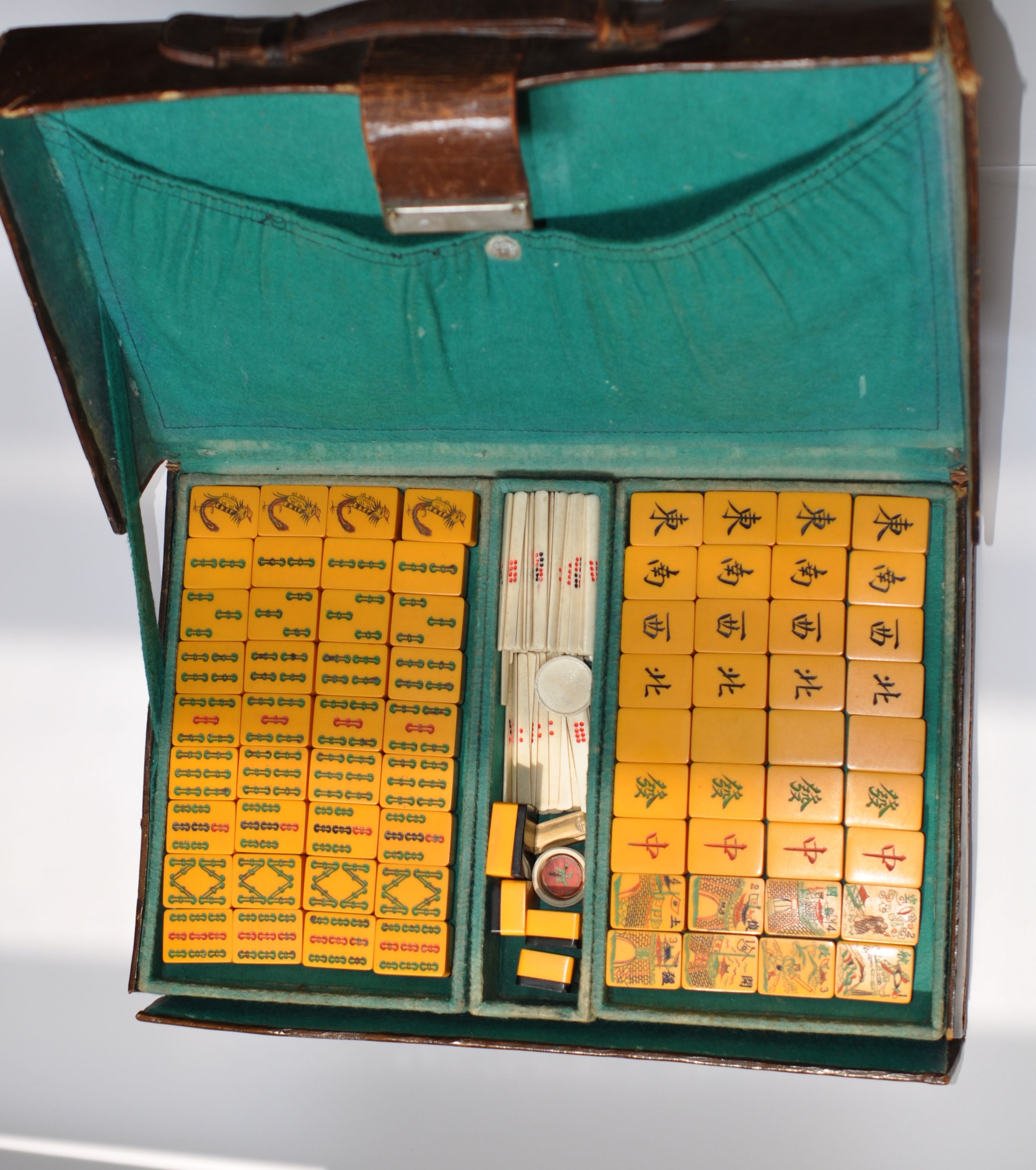

A small leather beat-up Mah Jong case tells another tale about another family who might have escaped the horrible chaos of 1941 Shanghai.

Sometime before the Autumn of 1939, a certain Mr. E A. R. Fowles, for reasons currently unknown to us, booked first-class Stateroom No. 205 on the Japanese N.Y.K. liner M.S.Terukuni Maru scheduled from Shanghai to London. We know all this because his name is on the luggage sticker affixed to the Mah Jong case.

What is missing on the sticker is a date of embarkation. Also unknown is who he traveled with. Moreover, until I can find a deck plan of this liner, I don’t know if this was a suite or a single room.

We are not exactly sure who this man was, but according to immigration records, there was a Mr. E.A.R. Fowles residing in Shanghai who went there with his wife and three children in 1925 on the P&O Liner Morea. We don’t know Fowles’ occupation, but most likely he worked in the British finance world along the Bund in Shanghai and lived quite elegantly with Chinese servants in the British Settlement District.

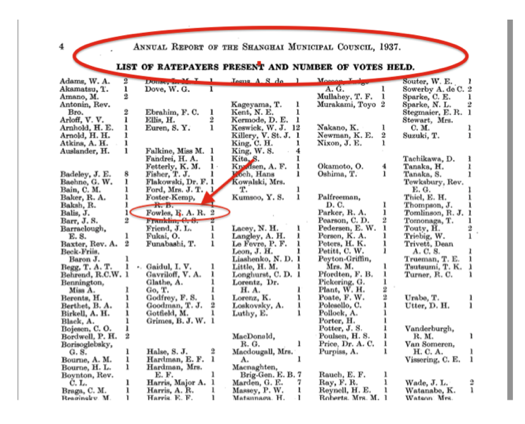

Here’s what else we know about our Mr. Fowles; he was a prominent “rate-paying” resident on Shanghai’s Municipal Council, present at its Annual meeting on April 14, 1937 and accorded “two votes” out of a total of 251.

At any rate, the total number of that august Shanghai Council, with a list composed mostly Anglican surnames, numbered just 334. Since there were 60,000 business people—not including Chinese— living in Shanghai since the early 1930’s, the Fowles family was on quite an exclusive list.

E.A.R. Fowles’s name doesn’t appear anywhere again on the 468 page report.

Fowles, along with the Council was charged with maintaining a standard of living for the Brits in the long-established “International Sector” extant since the 1800’s— from The Library and Orchestra Committees, to the drinking water, medical services and the police force. It also charged its ex-pat community to coexist with the Chinese, their Chinese servants and the increasingly hostile Japanese military. The 1937 minutes for The Council state what must have become a fast developing ad-hoc mission:

" The duty of the Council during these abnormal times is to adopt every means in its power to ensure the safety of life and property within the area under its control, and to preserve the peace, order and good government of the International Settlement…All persons are urged,… to bear cheerfully any inconvenience to which they may be subjected and to assist generally in preserving calm, peace and good order.”

Looking back, their society was a powder keg about to be lit. Indeed, the “Emergency Branch” report of the Council continues:

[The Ambulance Service] was constantly in demand and handled no less than 901 casualties suffering from bomb, shell, shrapnel…from hundreds of injured at the aerial bombing at the Bund and Nanking Road,…and the striking, by an unidentified projectile,…on August 23, at which calls the casualties were so numerous and the conditions so appalling that no record of the number of patients actually conveyed in ambulances …could be kept.

Perhaps it was a family emergency abroad, or perhaps Fowles sensed the forthcoming onslaught. We don’t know if he even picked up the ship in Shanghai. Whatever happened, his proper British world was unraveling, and people were fleeing Shanghai — just as many were fleeing Nazi Germany. He must have decided it was now the time to leave. (Ironically many Jewish people fled east by ship to Shanghai during this period, and the story of the Shanghai Ghetto is a miraculous one. The Japanese, as cruel as they were during those years, were not anti-Semitic. While there were indeed wartime hardships in Shanghai for Jewish people, the Japanese would not tolerate their persecution).

At any rate, Fowles’s itinerary from China to England called for a fortnight transit across the Indian Ocean into the Suez, the Mediterranean, and up into the Thames to London with numerous ports in between. How could Japanese ships be allowed to sail into European waters in the late 1930’s when England was at war with Germany? From 1937 until 1940, Japan was still regarded as a “neutral” country by England. Basically even though Imperial Japan’s atrocities in Mainland China— in their quest for oil and resources—resulted in such appalling massacres as in Nanking and Manchuria, diplomatic relations between the countries held and trade continued. It was only after the Japanese signed the Tripartite Act with the Nazi Germany Axis in 1940 that Japanese ships were targets for British warships.

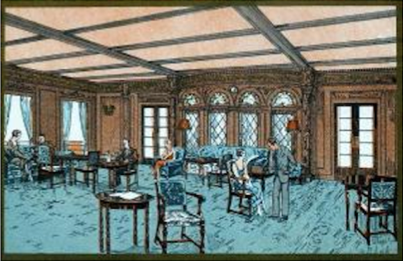

The vessel Mr. Fowles booked passage on was 505’ long, built in 1929, and thoroughly air conditioned throughout for her southern route which took two weeks. While not as grand or luxurious as an Atlantic Greyhound, Terukuni Maru could carry 121 First-Class passengers, 68 Second Class with a Japanese crew of 177. I think his trip happened sometime after 1937, which I’ll explain below.

Most likely, Fowles’ splendid Chinese Bakelite Mah Jong set remained in his stateroom.

I certainly don’t think it ever made out of his room and into the ship’s more public First Class Salon depicted below.

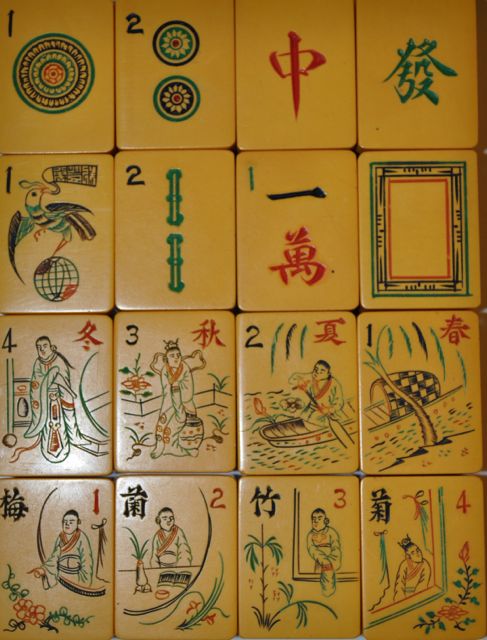

Why? Because the tiles have Chinese propaganda vilifying his Japanese hosts. Japan marched into Shanghai on July 7, 1937, and took it over. It is highly doubtful a set such as this one could have been made in Mainland China after that date. This is why I think the set must have been manufactured, most probably in Hong Kong in 1938, soon after Japanese hostilities began with China and why I place him on the this ship at about this time.

This item could be considered contraband. It’s subject matter was taboo to the Japanese and certainly to the crew. How did it get onboard through customs? Was Mr. Fowles so important his luggage was never checked? Was he a diplomat? Again we can only guess.

The message on the tiles takes no guesswork, however.

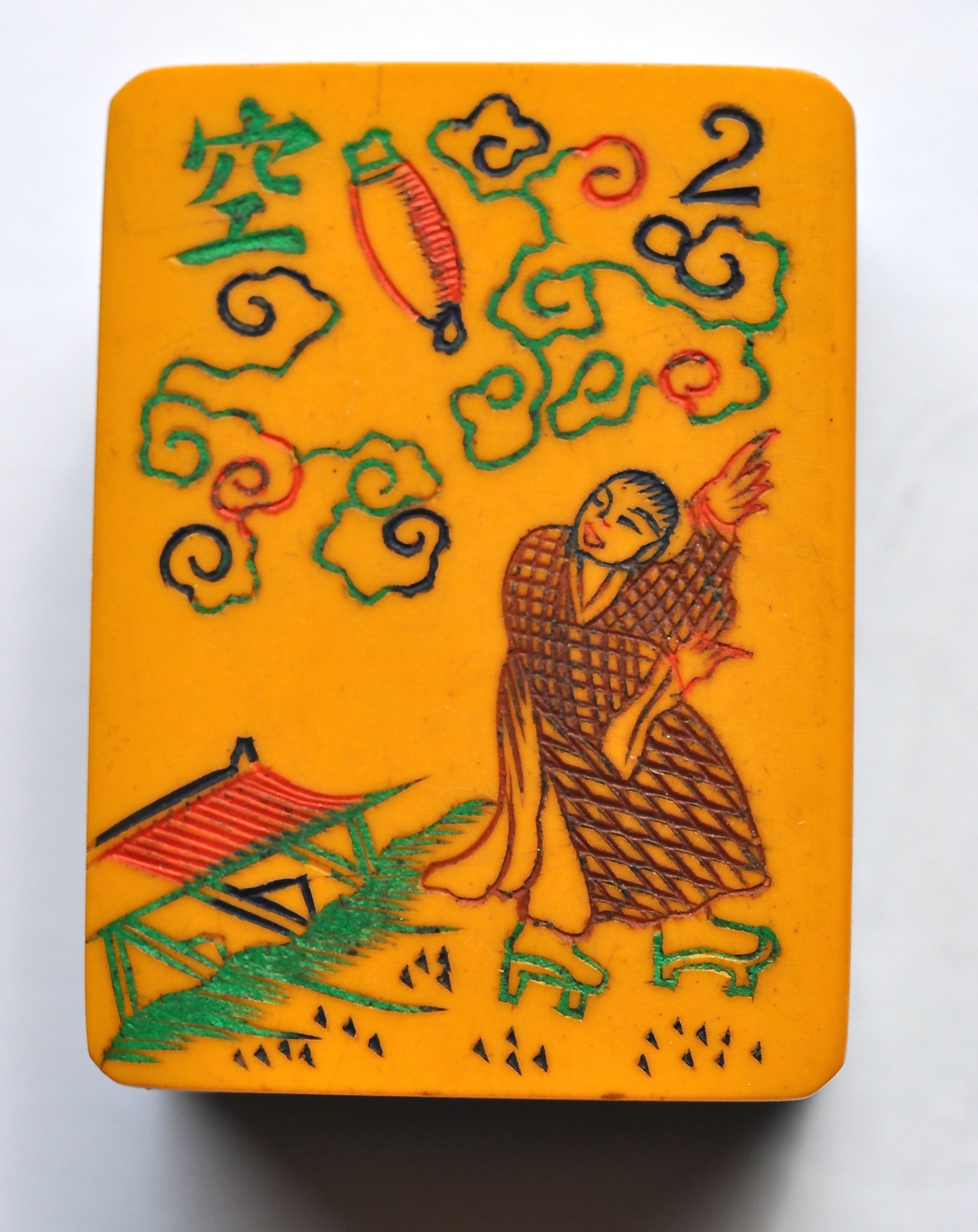

Look closely at this Flower Tile of what can only be a kimono and clog-clad Japanese man running from a house with a bomb aiming right at him.

Other Flower tiles are equally anti-Japanese:

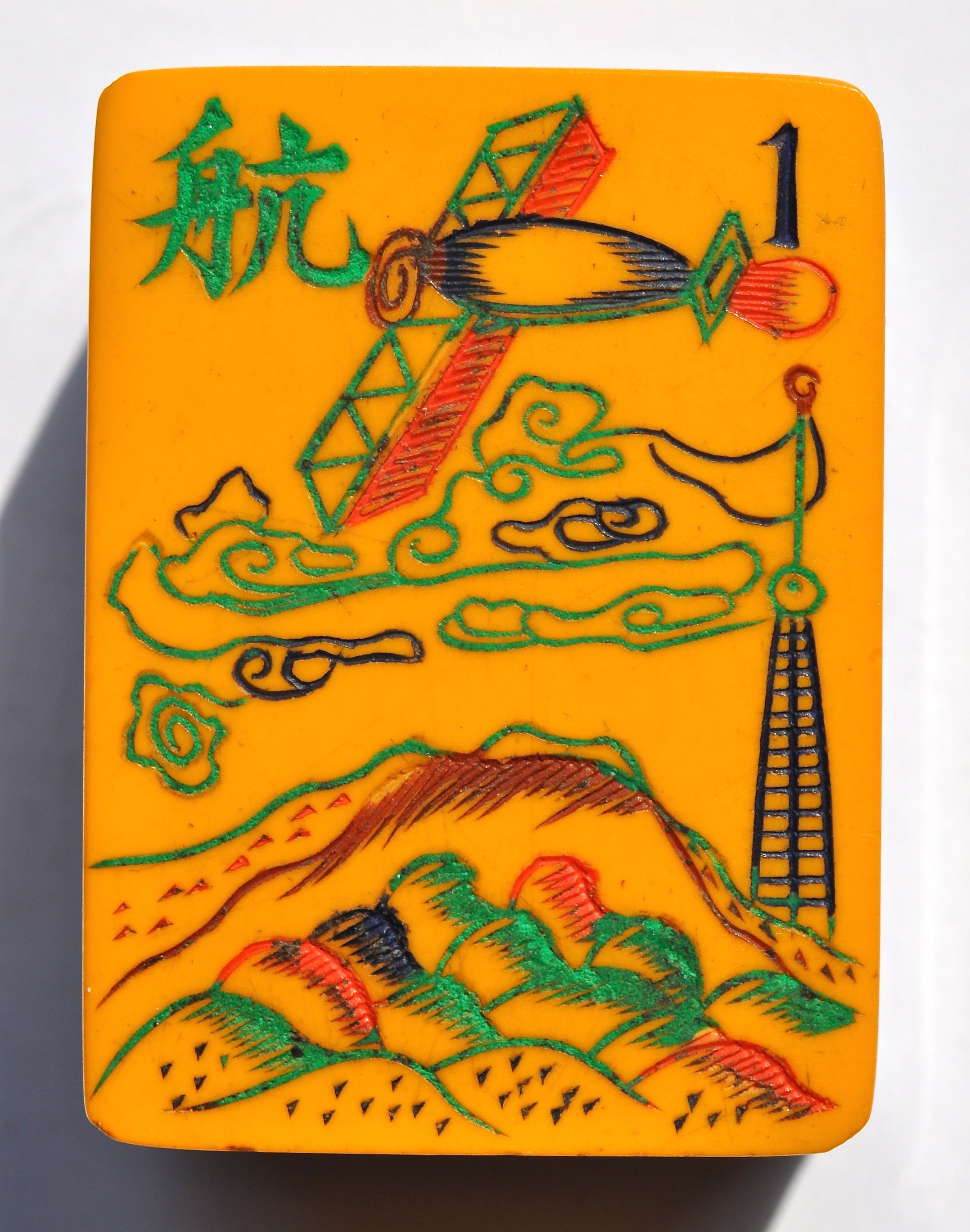

The tiles depict Chinese troops defending their country. The top row reads: "Aviation to save the country." This expression was also used on War Bonds in 1941 to help the war effort against the Japanese. The bottom row calls for "a move of the troops to save territory."

The top row shows a portable canon launching artillery and an aerial bomber over a mountain range. Below is a close-up of that tile.

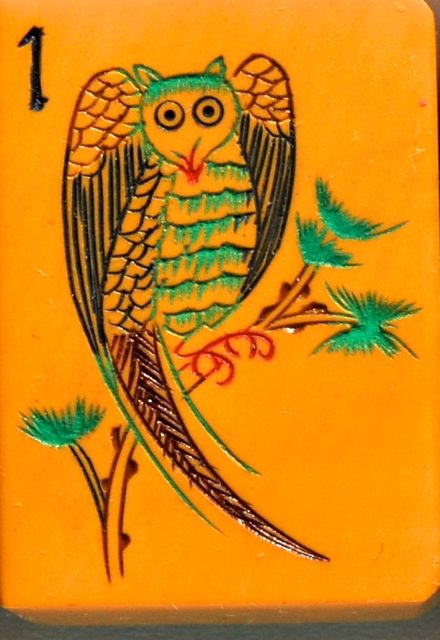

The phoenix and dragon are also beautiful and an interesting addition to the set. Remember the Emperor was associated with the Dragon, seen in the One Dot, and the Empress with the phoenix, seen as the One Bam. Interesting—since the monarchy had been gone for years, but perhaps a subtle reminder of old days?

Certainly this set was important to Mr. Fowles; his name was embossed in gold leaf on the back of the set’s leather case.

Maybe this Mah Jong set expressed his personal hopes for a free and independent China. If this is the Mr. Fowles we think it might have been, he’d lived there and raised a family for 13 years and most likely was devastated as to what was happening to his adopted city. I’d like to think that perhaps Fowles played the game in his stateroom with his family or like-minded refugees from Shanghai shouting “Mah Jong” while their room steward, a Japanese spy, listened with an ear to the door totally clueless as to what was really being thought, and what tiles were being played with.

Again, this is all vivid conjecture—we just don’t know.

We have no record of a E.A.R. Fowles debarking in London, or whatever happened to him and his family, or if he ever returned to China. We do know no Fowles were on Terukuni's May 1939 voyage as this name doesn’t appear on that passenger list. And, unless any of you have any further information on Mr. Fowles, our story ends there.

Or does it?

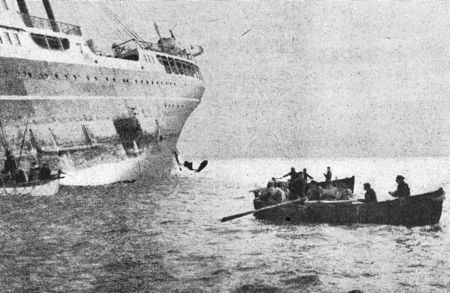

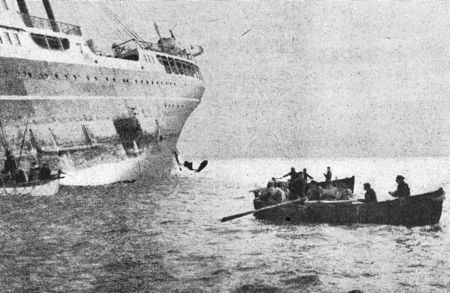

Remember I said that Fowles had to have left Shanghai before Terukuni Maru’s fall sailing on September 29 1939. That was to be her final voyage; for it was 62 days later on Nov 21at 12:39 am, following inspection by Royal Navy Minesweepers off the coast of England (remember, in 1939 she was still considered neutral), she hit a floating magnetic mine, and blew up. Terukuni Maru rolled over, twin screws in the air and was gone within 45 minutes.

There was not a single life lost among the 28 passengers or 177 crew, which my friend and ocean liner expert John Maxtone-Graham told me was “quite remarkable.” Four of the eight lifeboats could not be launched as she heeled onto her starboard side. Her sinking has been described as Japan's only World War II casualty outside East Asia before the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.

I don’t think Fowles was aboard her final voyage. His surviving Mah Jong case proves it. He had 45 minutes to get off the ship. Would he go back for his beloved Mah Jong game and take it into the lifeboat? I don’t think so, for two reasons: First, the liner sank too quickly — although one passenger described a steward having the time to run quickly back to a rapidly-filling cabin to get her life vest. Second, and more importantly, if he was traveling with his family, he would first want to make sure his daughters, wife and son were put into the lifeboats. That would be his priority. While there was no panic and the Japanese crew reportedly behaved in the best traditions of the sea, certainly the scene on the boat decks was one of grave urgency. At any rate, we have currently have no record of who the survivors were and Fowles doesn’t appear in any photos or newsreels of the disaster.

On the other hand, if the set was as dear to him as I think it was, maybe he did grab it. After all, it’s not large — only 9” x 14” and could easily fit onto his lap.

The wonders of the internet may reveal the final chapter about the real Mah Jong Treasure of a certain mysterious E. A. R. Fowles.

Our thanks to Ray Heaton for providing translations and images, and to Michael Stanwick for his research.

The book written by Gregg Swain and Ann Israel can be found on Barnes and Noble:

and Amazon

The website for the book includes reviews of the book, and author signings and other appearances.

Bibliography:

General History of Shanghai

Shanghai Municipal Council Report for the Year 1937 and Budget for the Year 1938 Part 1: Shanghai North China Daily News & Herald, 1938

|