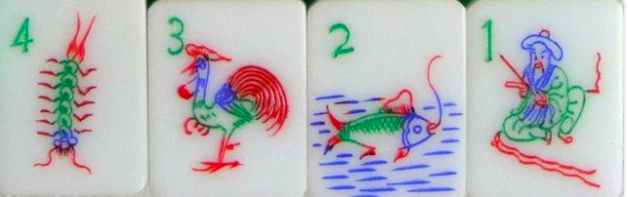

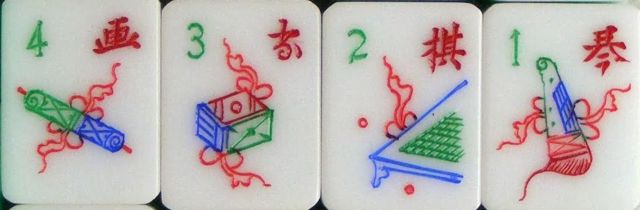

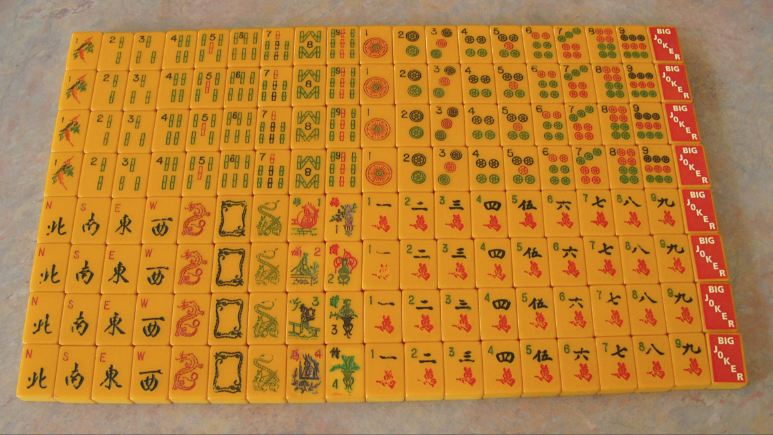

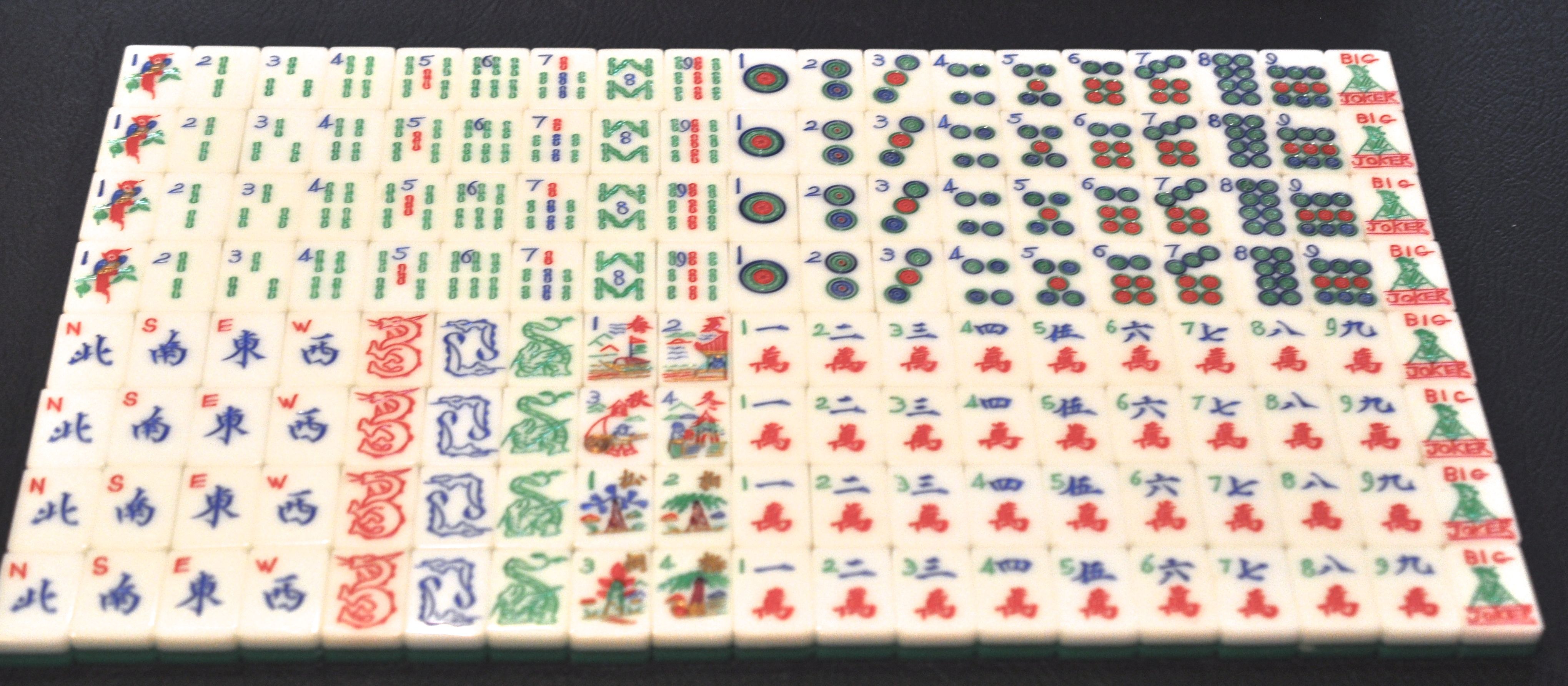

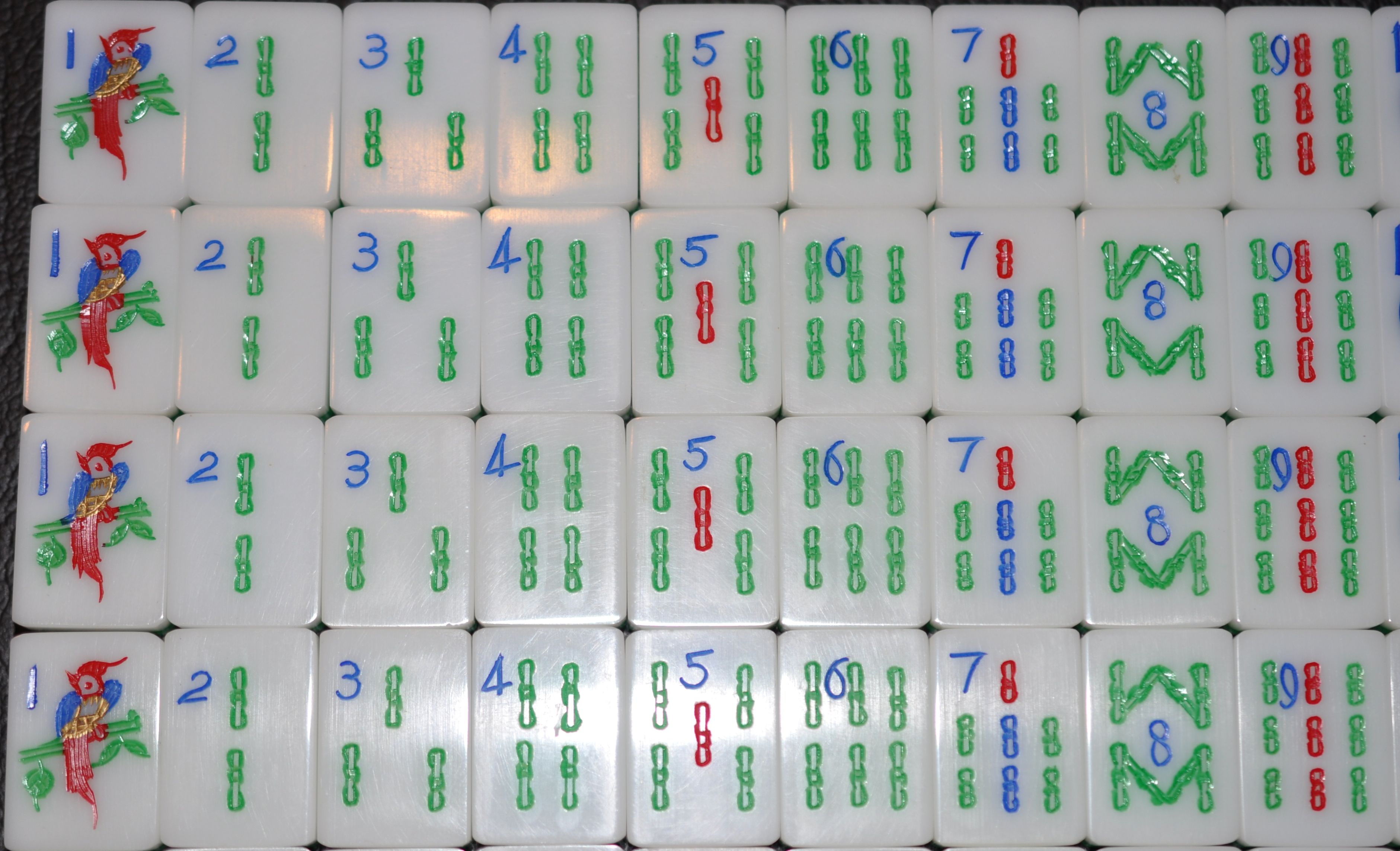

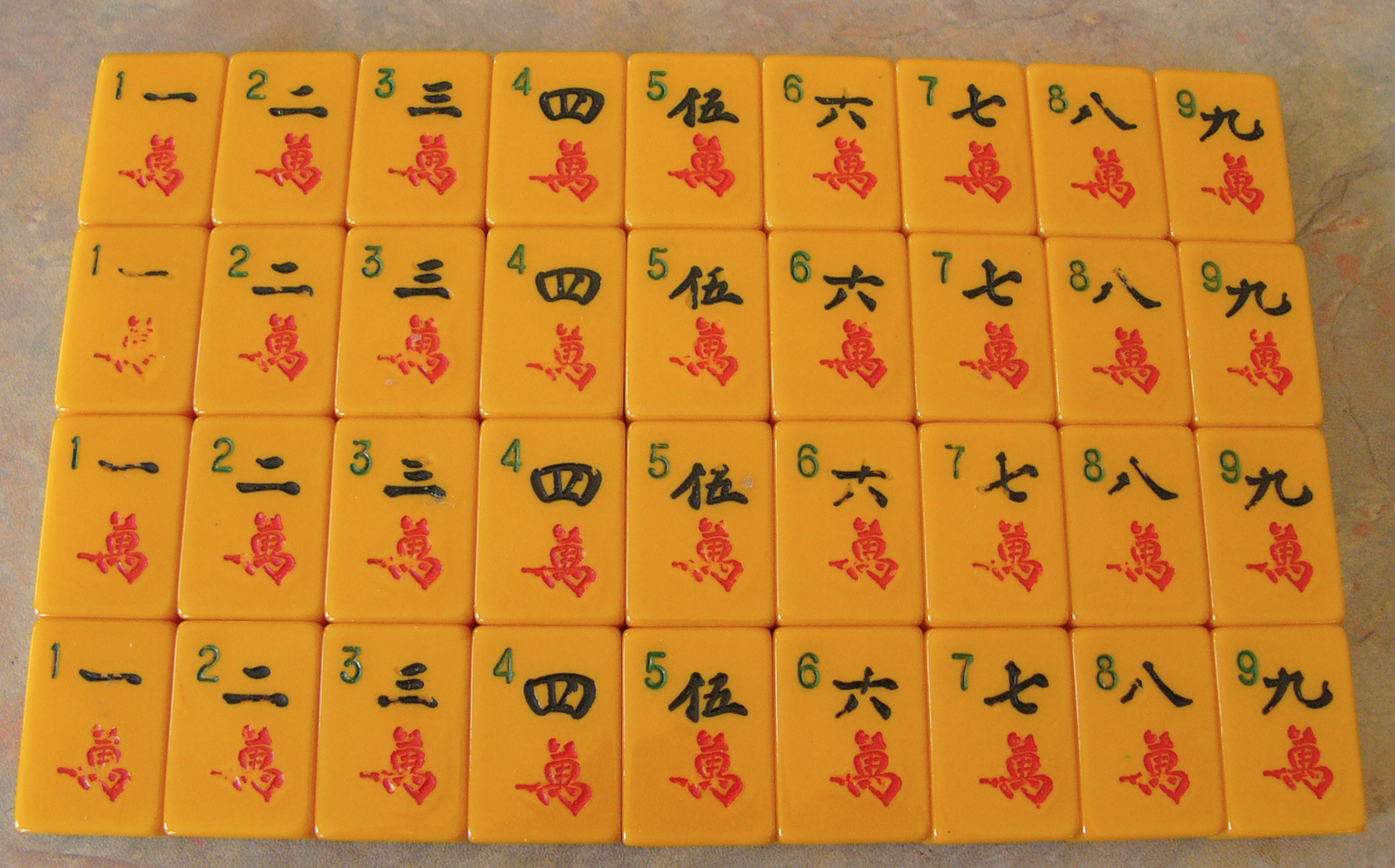

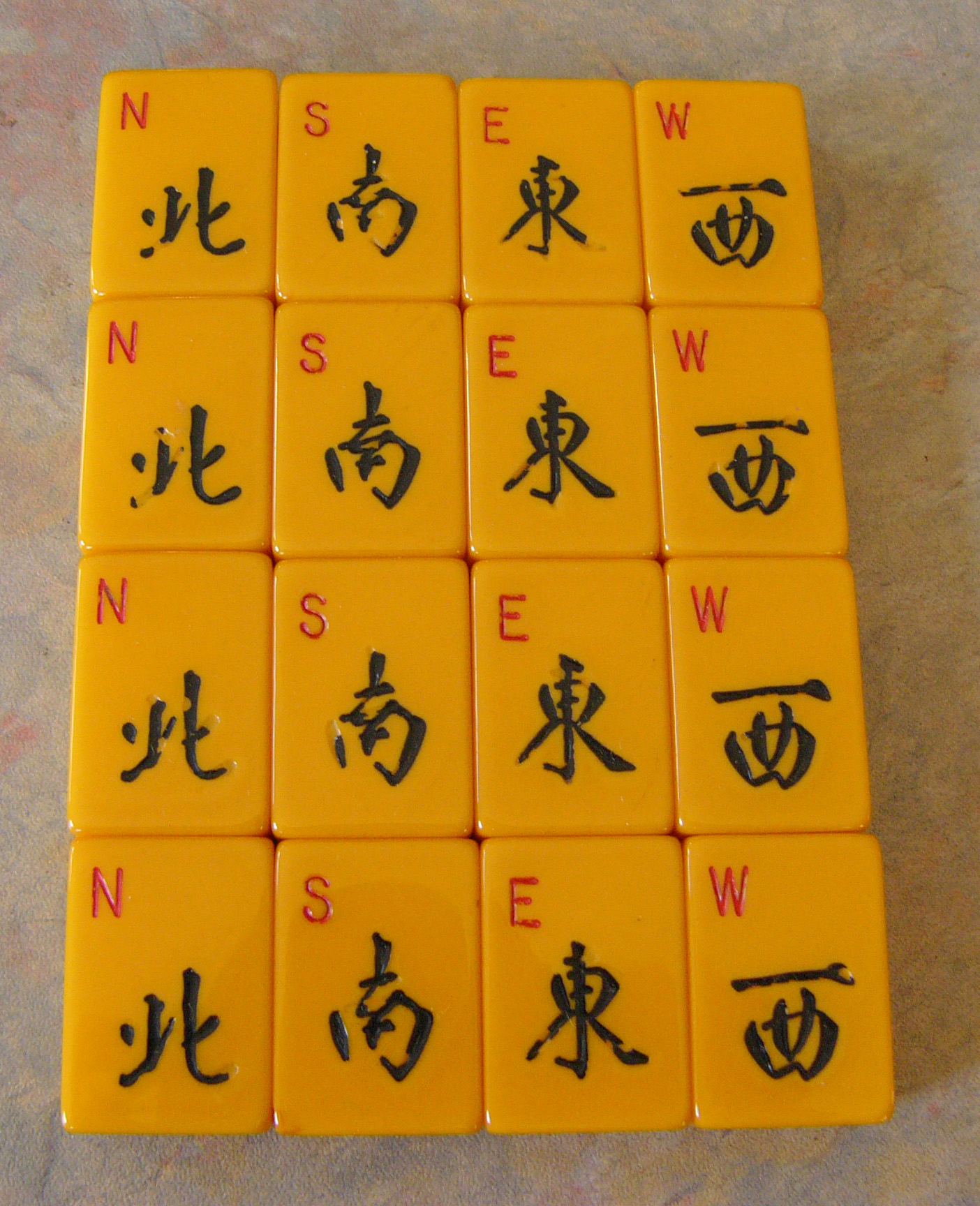

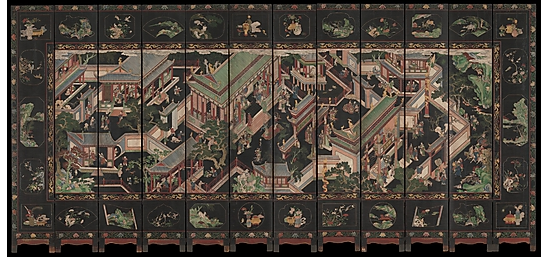

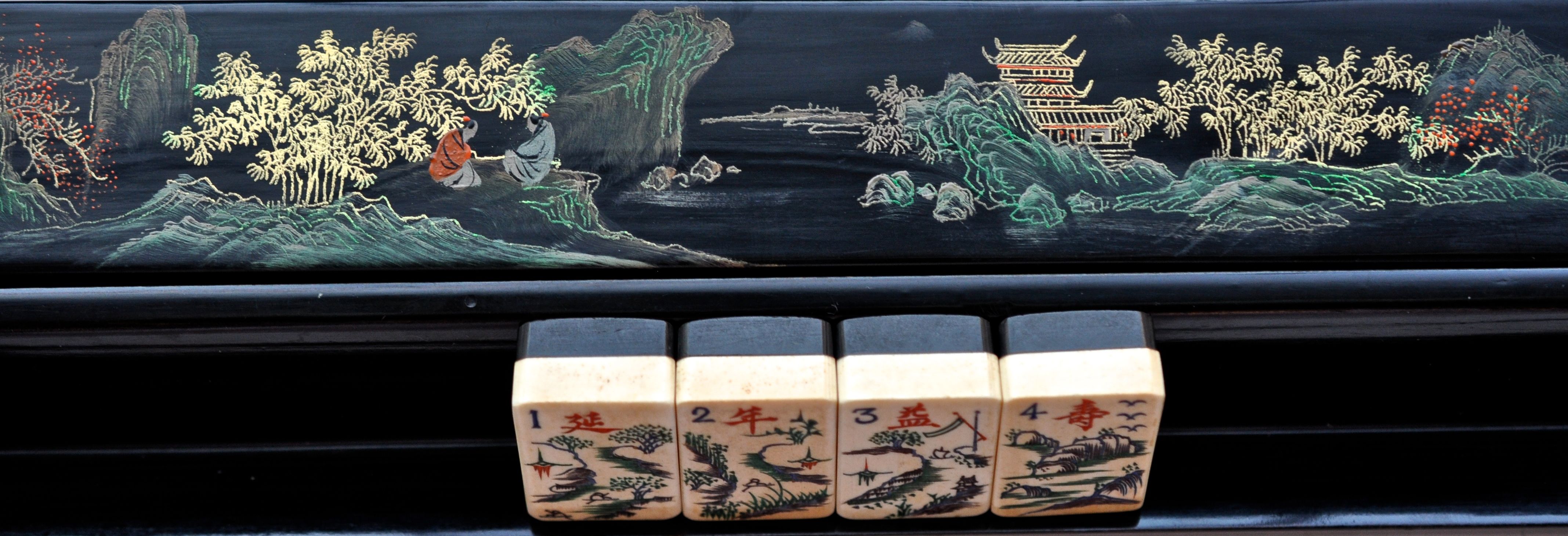

This post was written by Ray Heaton, and images were added. These four arts often appear in various forms on Mahjong tiles.

The Four Arts (四藝, siyi), or the Four Arts of the Chinese Scholar, were the four main leisure pursuits of the Chinese scholar gentleman. These are occasionally known as the Four Attainments of Pleasure.

Although the individual parts of the concept (Qin, Qi, Shu, Hua) have very long histories as activities befitting a learned person, the earliest written source putting the four together is Zhang Yanyuan's ''Fashu Yaolu'' or "exemplars of calligraphy", from the Tang Dynasty. The concept of these being "the four arts" is first found in the ''Xianqing ouqi'' or "on the pleasure of idleness", by Li Yu, sometime around the mid 1600's.

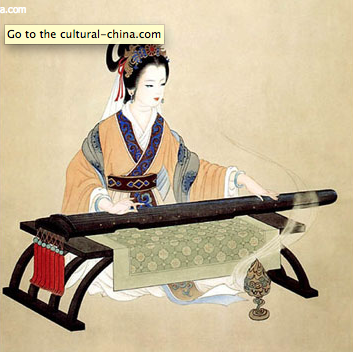

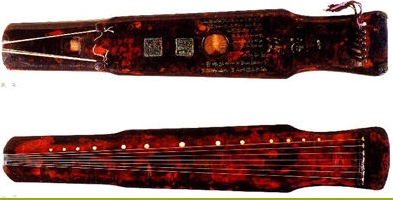

琴, Qin, the Guqin, a seven stringed instrument (rather like a Zither or Lute) and is China's oldest stringed instrument, with a documented history of about 3,000 years. It became part of a tradition cultivated by Chinese scholars and literati since the time of Confucius. Its reputation rests not only on the rich and diverse musical expression it is capable of, but also on the fact that it has been revered as a symbol of Chinese high culture – the essence of Chinese thought and philosophy are integral to the Qin repertoire itself. The Qin was Banned during the Cultural Revolution as belonging to one of "The Four Old Evils" or "The Four Olds".

The qin as seen on the Cultural China website

and on Wikipedia.

棋, Qi, the strategy game of Go or Chinese Chess, this will be either 圍棋 Weiqi the game of Go or 象棋, Xiangqí, Chinese Chess. According to Patricia Bjaaland Welch in Chinese Art, A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery, the game shown is most likely Weiqi. The Chinese Imperial Court used Weiqi as a gauge to measure the intellectual strength of an imperial scholar, requiring good mental discipline, a deep philosophical attitude and a multi-campaign mentality.

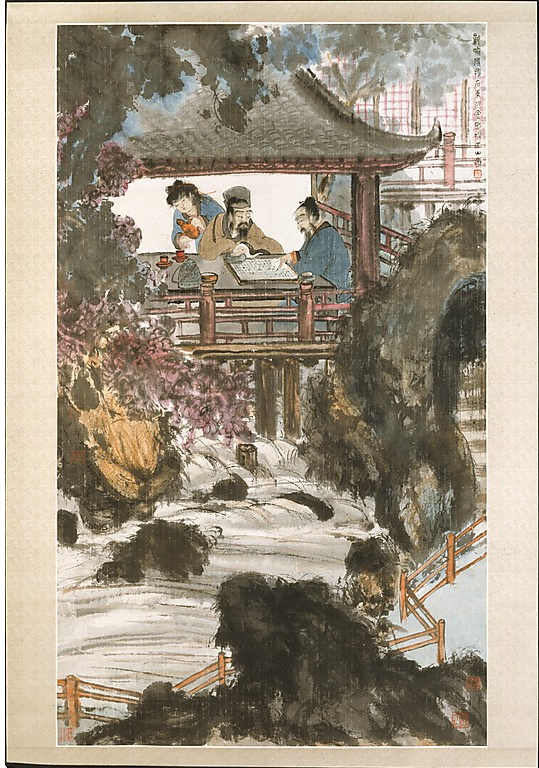

The image of scholars playing Go is from Wikipedia. Be sure to notice the young children hiding, and the taihu rock on the upper left.

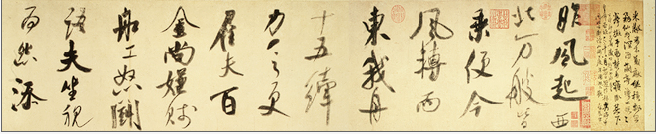

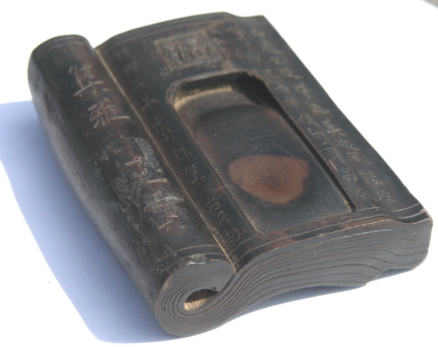

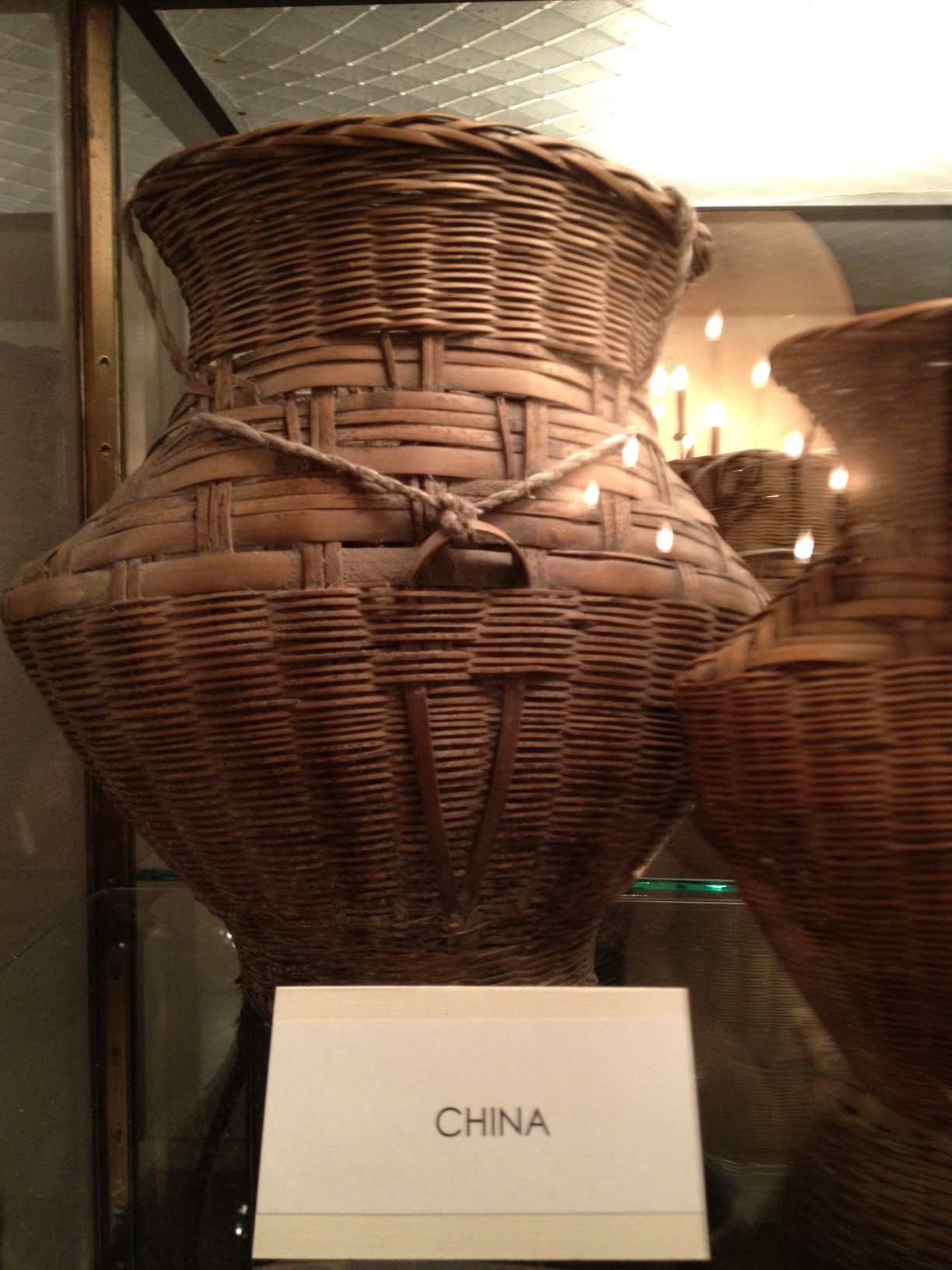

書, Shu, means to write and also means book but is used to refer to Chinese calligraphy, the representative image is often illustrated by books wrapped in silk or paper and tied with a ribbon. Calligraphy, or the art of writing, was the visual art form prized above all others in traditional China. The elevated status of calligraphy reflecting the importance of the word in China and scholars, whose main currency was the written word, came to assume the dominant positions in government, society, and culture. Associated to this are the Four Treasures of the Scholar's Study, also referred to as "The four jewels of the study" and comprise the Brush, Ink, Paper and Inkstone.

Following are some visuals, versions of which may be seen on Mahjong tiles:

From free stock photos above is a stack of books, which in Chinese art would be wrapped in fabric,

an inkstone above featured on thefullwiki.org,

and a calligraphy scroll itself, a poem in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum.

And just to make sure there is an understanding of how and why these images can get confusing:

from ancientpoint.com an inkstone shaped like a stack of books/scrolls! This leads us to:

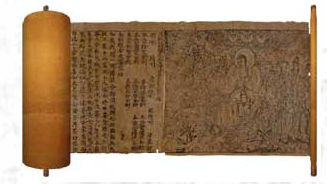

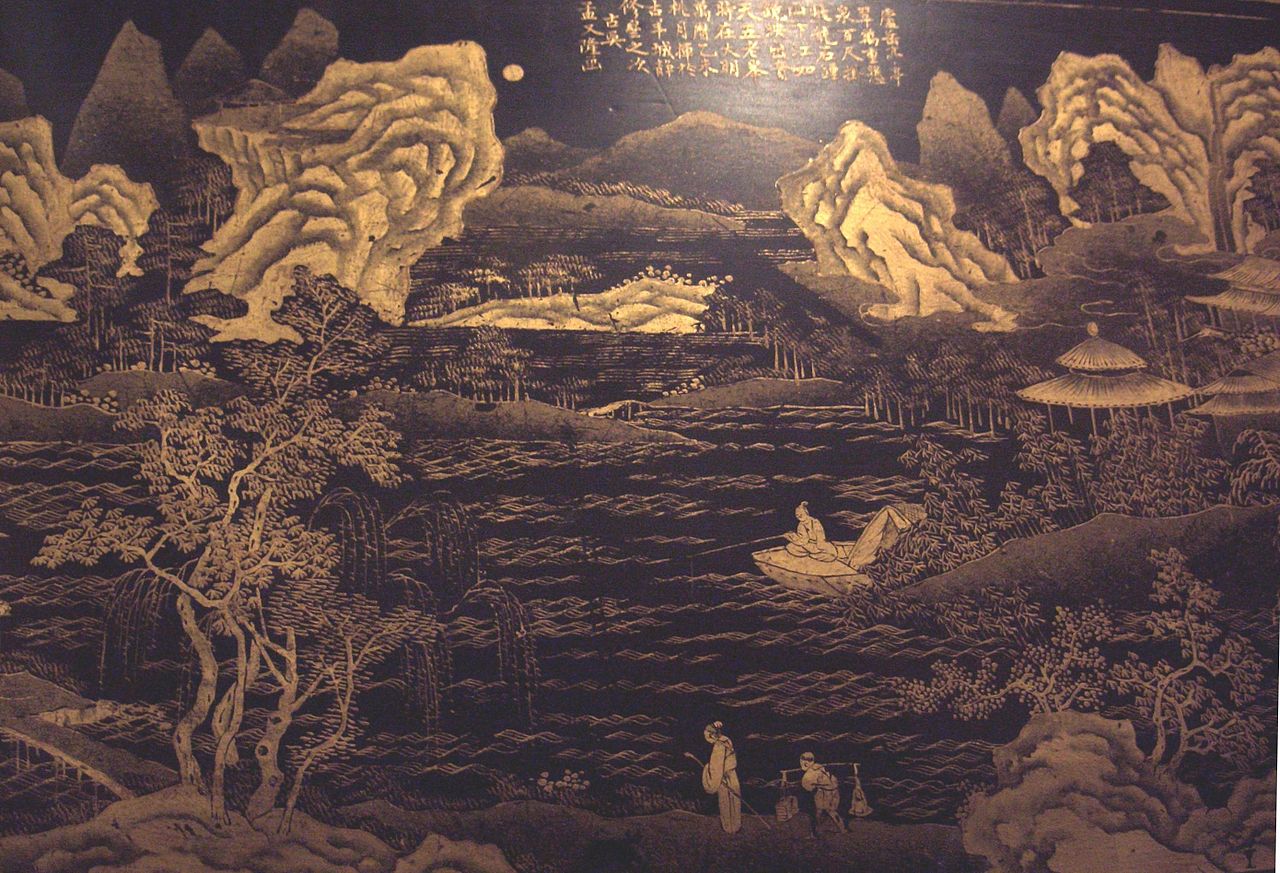

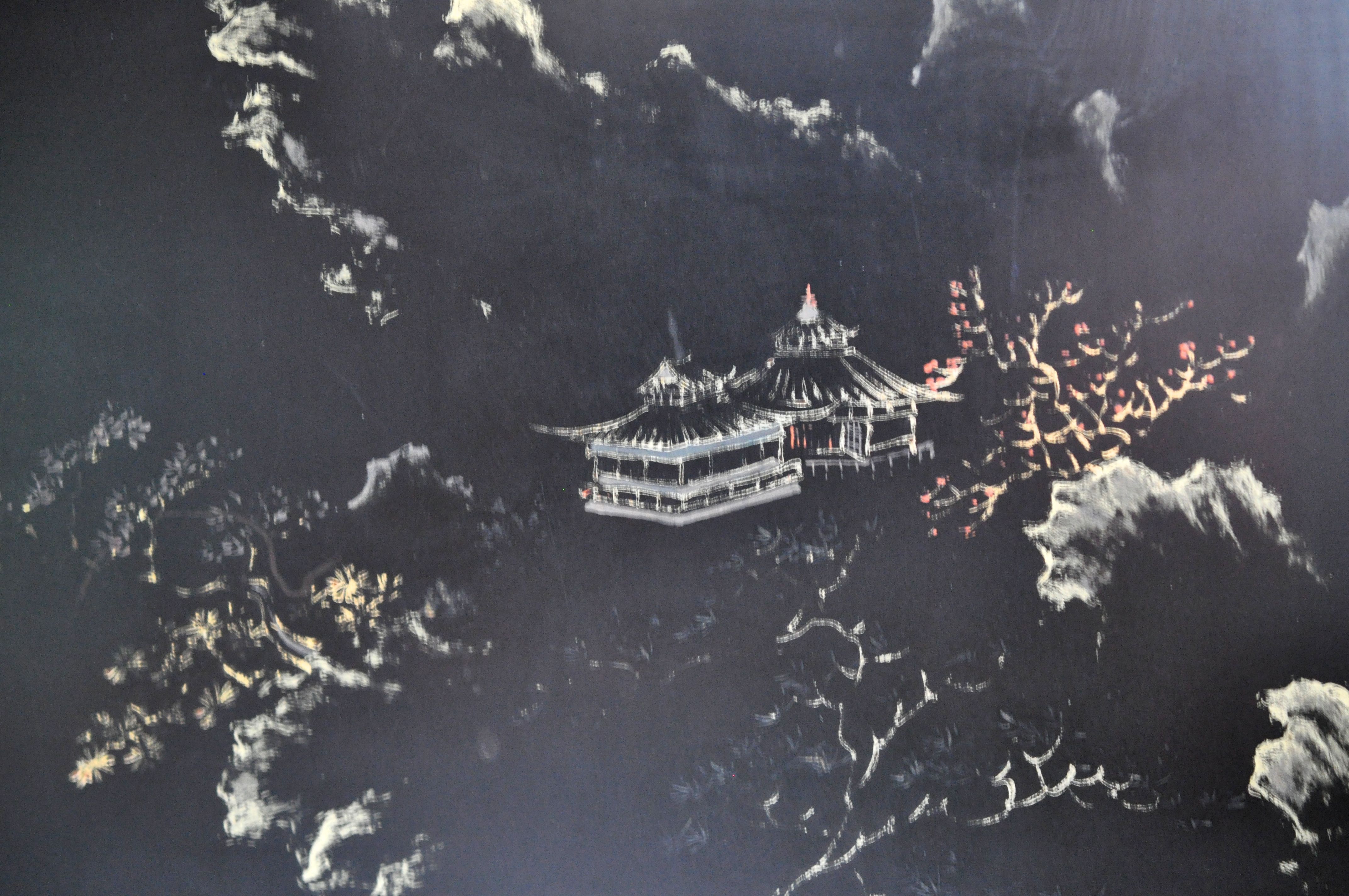

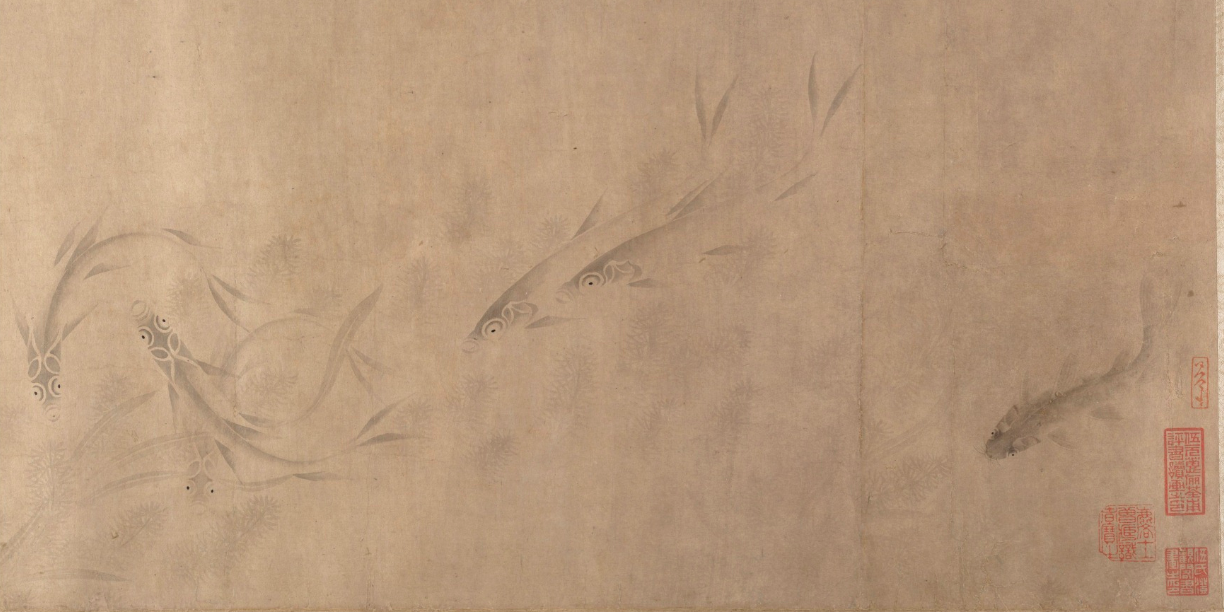

畫, Hua, Chinese painting. These are often a rolled scroll, sometimes also wrapped with a ribbon. Scholar-official painters most often worked in ink on paper and chose subjects—bamboo, old trees, rocks—that could be drawn using the same kind of disciplined brush skills required for calligraphy. This immediately distinguished their art from the colourful, illusionistic style of painting preferred by court artists and professionals. Proud of their status as amateurs, they created a new, distinctly personal form of painting in which expressive calligraphic brush lines were the chief means employed to animate their subjects. Another distinguishing feature of what came to be known as scholar-amateur painting is its learned references to the past. The choice of a particular antique style immediately linked a work to the personality and ideals of an earlier painter or calligrapher. Style became a language by which to convey one's beliefs.

from wikipedia. The scholar seems to be copying a scene from the unrolled scroll, perhaps an attempt by this scholar to link to the earlier work of another. We see the taihu rock here as well, and the Chinese barrel shaped stool we also saw in the drawing of the scholars playing Go.